Introduction

What it is possible for us to know about the historical incidence of child sexual abuse since the First World War? A starting point for any attempt at quantification has to be the annually published criminal justice statistics, which give national figures for cases reported to the police and persons prosecuted through the courts of law. However, there were no clear legal categories that map on to present-day understandings of child sexual abuse. The law had been constructed as a reaction to Victorian moral anxieties – including concerns about homosexuality – rather than the need to protect and safeguard children. This means that children (as those against whom offences were committed) were only partially visible within the criminal justice statistics. Anxieties about child abuse were often elided with the demonisation of homosexuality even after its partial decriminalisation in 1967. In sum, the British state did not effectively monitor abuse of children. Careful analysis of the criminal justice statistics does, however, enable us to understand how and with what very limited success the law was used in the past. Ultimately it is only possible to conclude that the law and criminal justice system were woefully inadequate in dealing with child sexual abuse.

Because of the difficulties of tracking child sexual abuse through criminal justice statistics across time, there has been little systematic attempt to do so before now. This is the first time that figures for the broad period 1918-1970 have been analysed to reveal the larger picture of how child sexual abuse was treated by police and courts.

Legal frameworks 1900-1960

Until at least 1960 what we now call child sexual abuse was subsumed within a complex and varied set of offences that had been inherited from the Victorian period and was adapted across time, through legal amendment, precedent and practice (see figure 1). Legislation focussed primarily on offences committed by adult men on females, or on the prohibition of all sexual acts between males (homosexuality). Age was a secondary consideration that was superimposed on top of existing gender-specific legislation – which was mainly concerned with whether parties were male or female.

The following gender-specific sexual offences could be applied to cases in which children were sexually abused: rape; buggery and its attempt; gross indecency (between males); indecent exposure.

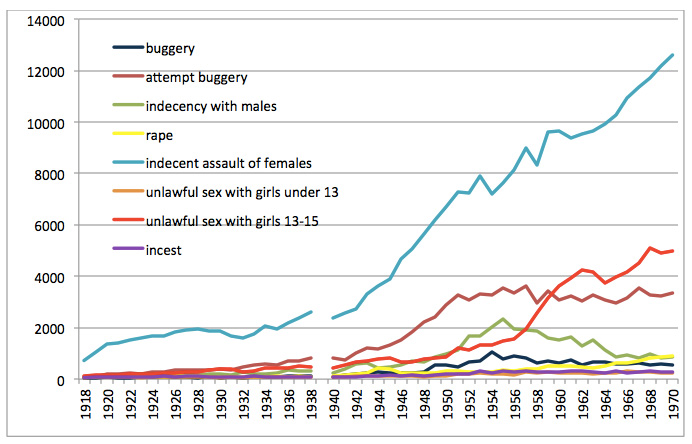

Fig 1: Number of sexual offences known to police, England and Wales 1918-1970: categories that may involve minors.

Until 2003 the charge of rape was a narrowly defined offence involving non-consensual vaginal penetration that could only be committed by a male on a female. Prosecutions were rare and it was mainly, although not exclusively used for offences against adult women. Even where rape was alleged, cases involving girls under 16 were more likely to be prosecuted using one of the lesser charges outlined below. It was assumed this made it easier to get convictions, but meant that the seriousness of offences was not always acknowledged. Attempts to prosecute the abuse of boys were overshadowed by the criminalisation of all sexual acts between males until 1967 in England and Wales, as well as the invasive policing of homosexuality informed by Victorian moral values. Same sex-practices between males were prosecuted through charges that were euphemistically described as ‘unnatural offences’ and which included ‘buggery’ or ‘attempted buggery' and ‘gross indecency’. These generic charges concealed offences involving minors; only by checking the specific details of each individual case is it possible to be certain whether a child was involved. After 1967 consensual sex between males was decriminalised if it took place in private and involved those over the age of 21. In 1994 this age was lowered to 18, and finally in 2001 to 16 (on the same terms as heterosexual relationships). The charge of ‘indecent exposure’ in a public place with ‘intent to insult any female’ was used to prosecute offences directed at girl children that did not involve physical contact (‘flashing’ or ‘exhibitionism’) although it was also applied to a range of other circumstances. No similar charge existed to protect boys. Indecent exposure was a minor offence dealt with by magistrates, who found several thousand men guilty per year by the 1940s.

The following sexual offences, where the law had been adapted to deal with age, were applied exclusively to cases in which children were sexually abused: unlawful sex with a girl under 13; and unlawful sex with girls aged 13-15.

Since the medieval period the idea of ‘age of consent’ had created the offence of ‘statutory rape’ (‘unlawful sex’) by fixing an age of protection for girls. In 1885 the age of consent for girls was raised from 13 to 16, where it has remained ever since. At the same time it distinguished between sex with those under 13 (which was viewed as a serious felony) and with those over 13 and under 16 (a less serious misdemeanour). Sexual acts that involved other forms of physical contact (touching) might be prosecuted as ‘indecent assault’ (on either ‘males’ or ‘females’) under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. The 1908 Children Act enabled these cases to be dealt with by magistrates in a court of summary justice (rather than the higher court of quarter sessions or assizes) if they involved boys or girls under the age of 16. This at least rendered these cases visible in criminal justice statistics: all indecent assault cases heard in magistrates courts related to minors.

A small number of cases of familial sexual abuse were prosecuted each year under the 1908 Incest Act; from the 1920s to the 1960s a mean average of 112 people were proceeded with nationally for ‘incest’ (with little variation across this period).

Legal loopholes and the Indecency with Children Act 1960

In the early 1950s case law began to challenge what had previously been a more flexible use of indecent assault and indecent exposure legislation to successfully prosecute child sexual abuse, with worrying effects. In 1951 magistrates in Clitheroe, Lancashire, dismissed a charge of indecent assault on a nine-year old girl, because they said she had willingly accepted an invitation to touch an adult man who approached her when she was walking along a river bank. The decision – referred to as the case of Fairclough v. Whipp – was upheld on appeal because there had been ‘no hostile act’ and was reinforced in a further appeal case in 1953. In the case of boys who accepted invitations to engage in sexual touching, it was argued that only a gross indecency charge could be pursued in a higher court; for girls there was no recourse in law. The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) acknowledged in 1956 that there were ‘a substantial number of cases’ that were not being prosecuted as a result of the change in legal precedent. The number of persons prosecuted for the indecent assault of girls under 16 fell by eleven per cent between 1953 and 1954 (with 160 fewer cases in court) (see Fig. 1). Between 1954 and 1957 alone the DPP received information from the police relating to 70 cases of indecency involving children under 14 in which it was decided that no proceedings could be taken in the light of Fairclough v. Whipp. Doubt was also cast on the use of the ‘indecent exposure’ charge in cases involving girls deemed to be ‘too young’ to be ‘insulted’.

As a result of these loopholes the need for a new piece of legislation was discussed and debated, culminating in the Indecency against Children Act 1960. This was the first piece of legislation on sexual offences to refer to children as a gender-neutral category and hence to apply equally to males and females. The act made it an offence to commit an act of ‘gross indecency’ with or towards any child under the age of 14, or to incite a child to such an act. It did not, of course, protect those over 14 but under the age of 16. The act worked alongside existing charges, adding a further option rather than transforming the judicial response to child sexual abuse. This was not achieved until the radical overhaul of the law in 2003 with the introduction of ‘abuse of trust’ legislation.

Counting and measuring: the problem of prevalence

The inadequacy and complexity of the law regarding sexual offences made it impossible to monitor the proportion of cases involving children. This generated concern amongst reformers from the 1920s. The Departmental Committee on Sexual Offences Against Young People stated in 1925 that it was of ‘great importance that the public should have full information’ and recommended that the annual Criminal Statistics should contain ‘a complete return of all sexual offences against young persons reported to the police’. This was never followed through.

The 1925 Committee had also heard evidence from children’s charities and social workers which made it very clear that there were ‘very many more cases of sexual offences against young persons’ than those reported to the police. Even when reported, proceedings were taken in only ‘a small proportion of cases’. They heard from witnesses who suggested that – even before the test case of Fairclough v. Whipp – there had been difficulty in prosecuting cases that did not involve ‘hostile acts’ and that these were often dropped at an early stage . Clearly one of the problems of abuse cases is secrecy; there were rarely witnesses other than the child involved. Although there was no requirement (in theory) under English law that corroboration was needed, a number of test cases in the 1920s established that it was not safe (in practice) for juries to convict on the uncorroborated testimony of a young witness. This reliance on corroboration was not overturned until the 1980s.

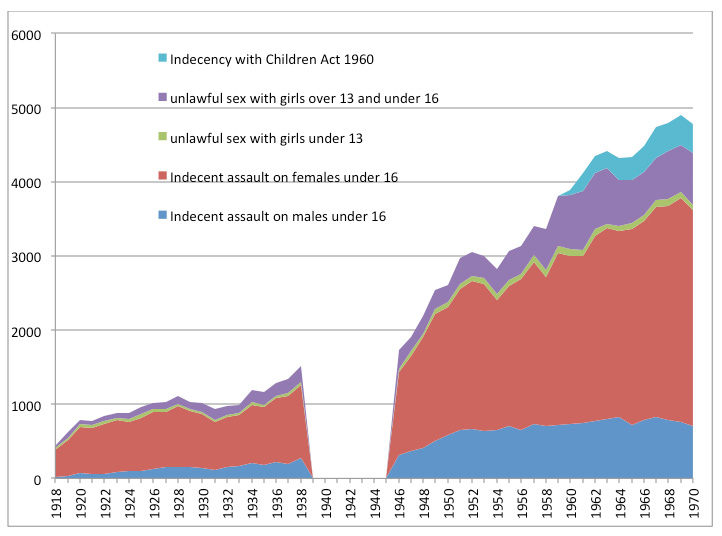

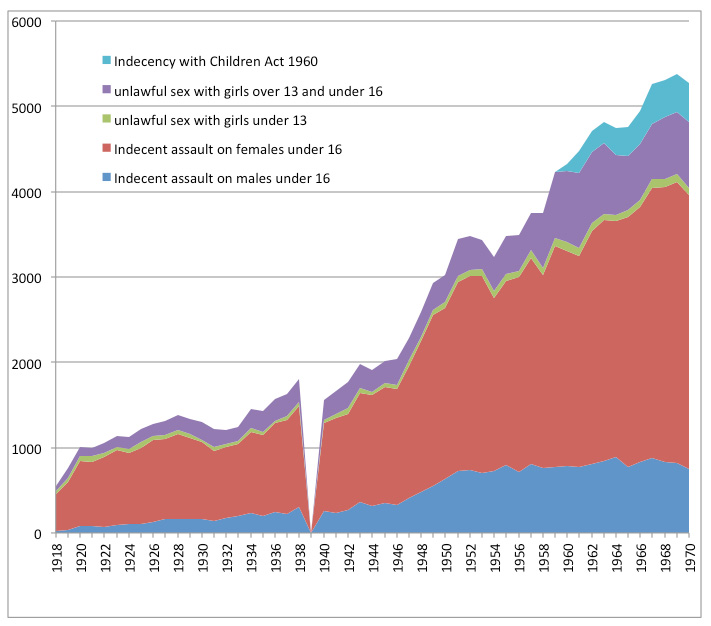

Despite these significant difficulties, analysis of the criminal justice statistics themselves is valuable in demonstrating, at a minimum level, the number of cases of child sexual abuse that have come to formal public notice across time. It is possible to identify court trials and findings of guilt for those accused of age-specific sexual offences (unlawful sex with girls under 16; indecent assault on males and female under 16; and the 1960 Indecency with Children Act). As Figure 2 shows, the minimum number of persons tried for child sexual abuse was 552 in 1918, rising ten-fold to 5271 in 1970. As Figure 3 shows, the minimum number of persons found guilty of child sexual abuse rose from 442 in 1918 to 4500 in 1970. Whilst 80% of cases that came to court trial were convicted across time, other evidence suggests that most cases were sifted out at earlier stages. Figures 2 and 3 effectively demonstrate the tip of the iceberg: the trial of 136,019 persons for child sexual abuse in the period 1918-1970, with 109,496 found guilty.

Fig 2: Number of persons tried for sexual offences against minors under the age of 16 in England and Wales, 1918-1970. Source: Criminal Justice Statistics for England and Wales. Note: data for persons tried in 1939 was never published.

Fig 3: Number of persons found guilty of sexual offences against minors under the age of 16 in England and Wales, 1918-1970. Source: Criminal Justice Statistics for England and Wales. Note: data for findings of guilt during the Second World War was never published.

To what extent does this data reflect an increase in the prevalence of child sexual abuse? Or is it the reporting of child sexual abuse that has increased across time? In relation to girls in particular, the difficulties of reporting appear to have decreased gradually , leading to rises in the number of indecent assault cases prosecuted in the late 1930s, immediately after the Second World War and then more gradually across the 1960s. Although there were remarkably few changes in the definition of offences across the twentieth-century (other than with the introduction of the 1960 Act), there were some advances in the procedures adopted by the police and the courts which undoubtedly encouraged reporting. For example, the 1933 Children and Young Persons Act made it clear that newspapers should not publish the name of any child involved in any court proceeding or any details that might lead to identification. By the 1950s it was likely that witness statements would be taken by female police officers who received some specialist training. Generally it became more accepted that the police and courts (rather than informal or community measures) were the appropriate mechanism to resolve complaints for a wide variety of offences, leading to increases in the business of the courts (and thus criminal justice statistics) across the board.

Whilst there may have been an increase in prevalence, this is harder to evidence. Newspaper reports of court hearings are crucial in suggesting that those cases that came to light tended to do so because children made disclosures to their mothers and also that the abuse had often taken place out of doors or in other public settings. It is very noticeable that there was no newspaper reporting of child sexual abuse in relation to residential children’s institutions until very late in the twentieth century. For those who had no close relationship with another caring adult to whom they might disclose abuse, it is unclear how cases might have been discovered. Reformers of the 1920s claimed that the crowded living conditions of the urban poor meant that children could not be sheltered from information about the sexual body and that overcrowding thus led to inappropriate sexual acts. Yet cases were often discovered precisely because they were seen or heard, by mothers, neighbours and relatives. It is possible that the rise of privacy and private domestic space has led to an increase in opportunity, secrecy and thus prevalence. Yet this trend has also been accompanied by a tightening up of concerns about unaccompanied children in parks and open spaces which has led to changing patterns of play and supervision. It is most likely that there has simply been a shift in the geography of child sexual abuse and its reporting rather than any tangible rise or decline in prevalence across time.

Criminal Justice statistics demonstrate that those prosecuted and found guilty were overwhelmingly likely to be male across the twentieth century. Women were very rarely prosecuted or found guilty of sexual offences against minors, but it is likely that the gender-specificity of sexual offences once again concealed child sexual abuse. Until the introduction of legislation relating to abuse of trust (2003) it was ‘a well-known fact’ that there was ‘no statutory provision forbidding a woman to have sexual intercourse with a male under 16’, as Lord Lane Chief Justice put it in 1981. Case law, too, suggests there may have been some ambiguity as to whether a woman could be accused of indecent assault of males under 16 although it was upheld in 1934 that such a conviction was sound where there was no consent. There was undoubtedly a gender-bias within the law; the classification of sexual offences was based in the main on assumptions about male sexual agency and female passivity. The highest incidence of the successful prosecutions of women was in 1948 when 14 females (and 1708 males) were found guilty before magistrates of indecent assaults on females under 16 (still less than 0.01 per cent of cases).

Conviction rates: the conversion of ‘cases known’ to ‘persons found guilty’

Finally, the criminal justice statistics can be used to gain an important indication of the types of sexual offences that were most likely to result in findings of guilt in the courtroom.

The annual Criminal Justice statistics recorded the numbers of ‘cases known to the police’ (for sexual offences other than indecent exposure). This is a problematic category since whether something was classified as ‘known’ was dependent on whether and at what stage a report was officially acknowledged and recorded. The processes for capturing this have changed across time. However, data for ‘cases known’ can be usefully compared with data relating to the number of persons ultimately found guilty in any court (see table 1). This is not a like-for-like comparison since an individual ‘case’ may have involved more than one assailant; and one person might have been found guilty of a number of ‘cases’. Nevertheless, this is the closest that historians can venture to ascertaining a ‘conviction’ rate for sexual offences in the period 1918-1970. In essence it provides a conversion rate for ‘cases known’ into ‘persons found guilty’.

It is rather more straightforward to compare the number of persons against whom proceedings were taken with the number of persons who were found guilty across different categories of sexual offences (see table 2). This gives us a very accurate picture of court proceedings and their results, although it ignores cases that were not taken forward.

Table 1: Persons found guilty as a percentage of all cases known to the police

|

year |

buggery |

attempt buggery |

Indecency with males |

rape |

indecent assault on females |

unlawful sex with girls under 13 |

unlawful sex with girls over 13 and under 16 |

|

1918 |

51.4 |

61 |

44.3 |

25.6 |

57.1 |

54 |

36.3 |

|

1928 |

22.4 |

60.7 |

54.6 |

17.8 |

49.2 |

43.8 |

36.4 |

|

1938 |

47.8 |

42.9 |

51.3 |

41.4 |

42.6 |

51.3 |

44.2 |

|

1948 |

48.1 |

27.8 |

48.6 |

30.2 |

31.1 |

39 |

30.7 |

|

1958 |

38.1 |

31.8 |

42 |

25.8 |

28.4 |

34.6 |

21.7 |

|

1968 |

36.8 |

28.5 |

65.6 |

28.3 |

27.5 |

31.3 |

12.7 |

Table 2: Persons found guilty as a percentage of all persons proceeded with.

|

year |

buggery |

attempt buggery |

indecency with males |

rape |

indecent assault on females |

unlawful sex with girls under 13 |

Unlawful sex with girls over 13 and under 16 |

|

1918 |

51.4 |

79.4 |

51.5 |

26 |

72.2 |

61.4 |

41.1 |

|

1928 |

27.1 |

85 |

63.6 |

20.4 |

73.9 |

54.2 |

45.9 |

|

1938 |

90.1 |

81.5 |

74.5 |

56.9 |

78.6 |

85.4 |

64.3 |

|

1948 |

83.2 |

85.9 |

81.1 |

54.7 |

80.2 |

65 |

72.6 |

|

1958 |

83.5 |

92.2 |

93 |

54.1 |

89 |

82.4 |

82 |

|

1968 |

74.4 |

95.5 |

89.3 |

56.5 |

89.4 |

80 |

87 |

Some very significant trends can be identified from these two tables. Firstly, it is clear that across time, cases involving rape (and usually involving adult women rather than minors) were the least likely to lead to conviction. The number of persons found guilty in 1968 represented only 28 per cent of cases recorded as ‘known to police’, and this had not improved across 50 years. Consistently across the period, just over a half of rape cases that led to court proceedings resulted in a finding of guilt. For all other sexual offences, around 80 per cent of cases that came to trial resulted in findings of guilt in the years after the Second World War. Nevertheless, although there was a significant increase across the century in the reporting of cases of both indecent assault on females and also of unlawful sex (‘cases known to the police’, see fig. 1), so the conversion of these cases into persons found guilty became less likely: 27.5 per cent of indecent assault cases in 1968 compared to 57.1 per cent in 1918.

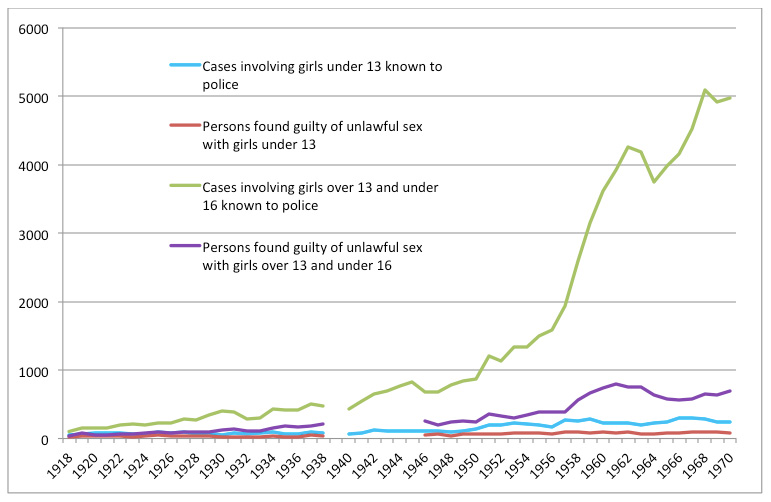

The most striking anomaly relates to the treatment of cases involving unlawful sex with those aged 13-15. By 1968 this was starkly the offence for which there was the lowest conversion rate of reported cases into persons found guilty: 21.7 percent in 1958, falling to 15 per cent in 1965 and then to 12.7 per cent in 1968. In the 1920s-1940s unlawful sex with girls aged 13-15 was also the least likely of sexual offences that came to trial to result in guilty verdicts. The reason for this reluctance to convict can be found in the indeterminate legal status attached to girls in this age group. As for adult women, court cases usually hinged on demonstrating consent or its lack. Moreover, under the 1922 Criminal Law Amendment Act, any male defendant who was under the age of 24 was permitted to use the defence that he had believed the girl was over the age of 16. It is certainly the case that by the 1960s this clause was used to prevent prosecutions of peers of a similar age. Nevertheless it was also used to protect some adult men in their early 20s from allegation of unlawful sex with girls as young as 13. As Figure 4 demonstrates, there was a very significant gap between the number of cases of unlawful sex with girls aged 13-15 that were reported and the number of persons found guilty. This gap widened profoundly in the 1960s.

Fig. 4: Relationship between cases reported to the police and persons found guilty: unlawful sex with girls under 16, England and Wales 1918-1970. Source: Criminal Justice Statistics for England and Wales.

Conclusion

The incremental increase in statistics relating to child sexual abuse across the twentieth century is most likely a result of the tightening up of police procedures around data collection (and the recording of complaints) as well as some improvement in the likelihood that cases that came to light would be reported to the police. In the 1920s and again in the 1950s the inadequacies of the law were clearly exposed, yet responses remained slow and piecemeal. Awareness of the existence of child sexual abuse ran alongside a reluctance to address it directly or recognise it formally. The 1960 Indecency with Children Act – the response to legal loopholes identified in 1951 – suggested a new way forward in beginning to focus on the child rather than gender, but its effects were limited. It was not until the 2003 Sexual Offences Act that the child was placed at the centre of legislation and the category of ‘abuse of trust’ was created. Across the twentieth century, criminal justice failed to deliver justice to children and young people.

The historical record for the twentieth century suggests that even when there was an awareness of the deficiencies of the law and an impetus to remedy them, opportunities were missed and change was alarmingly slow. It highlights how vital it is that action should take place rapidly on behalf of children: to investigate problems, identify real solutions, and create effective legislation that does not take a whole generation to enact.