The coalition's Health and Social Care Act became law on 27 March 2012. It marked the end of a particularly traumatic and bruising political battle, both in and outside Parliament, which began with the publication of former Health Secretary Andrew Lansley's Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, in July 2010. Noticeably, the White Paper offered no clear rationale for statutory reform, but was, as Nick Timmins notes, nonetheless 'stuffed with change'. Its key proposals included:

Oversight was to be put into place to guard against anti-competitive practices. Yet within the White Paper, Timmins concluded, there was no clear 'narrative, a definition of precisely what problem this mighty piece of legislation was meant to solve, and how'. Moreover, little attempt was made to engage with patient groups, the public, or hospital and community health staff.

Public support for the reforms remained slight. Polled by YouGov in February 2012, only 39 per cent of Conservative voters viewed it positively; for Liberal Democrat voters the figure plummeted to only nine per cent. Concurrent with the debate on reform, public satisfaction with the 'running' of the NHS recorded its largest one-year fall for thirty years, dropping from 70 per cent in 2010 to 58 per cent in 2011, reversing the trend of steadily rising approval ratings since 2001. John Appleby, the chief economist at the King's Fund, attributed this to the 'febrile political atmosphere' that accompanied the 'intense negative coverage of the coalition's health reforms.' It was, it seems, largely an 'emotional response.'

How that 'gut feeling' was constructed depended not simply upon contemporary realities but on the ways in which the British people imagined their past. So strongly embedded are some national myths - not necessarily as untruths but as simplified stories, often repeated - that they become statements of fact. As the philosopher Roland Barthes notes, myth abolishes the 'complexity of human acts'; it constitutes the 'loss of the historical quality of things'. Our popular appreciation of the NHS today is built around a mythic pre-NHS dystopia. As a recent BBC documentary, Health before the NHS, lamented, before 1939 a 'hospital was not always the kind of place you would go to get better', being frequently the 'last resort of the destitute', where care remained something of a 'lottery' amid a 'patchwork of services'. Thus, for the British, the creation of the NHS became a success 'story of how access to good quality health care became a right, transforming grim Victorian institutions for the poor into modern centres of medicine for all.'

One reviewer of Health before the NHS later commented in the British Medical Journal that the pre-NHS health care system was ramshackle, chaotic, and disorganised, leaving 'millions in terror of falling ill'. Yet this failed past, he suggested, had an 'eerie resonance with current moves to marketise the NHS' today, with a 'diversity of providers troubled by the very minimum of regulation.' A front page story in The Guardian quoted Dr Mark Porter, who then chaired the BMA's hospital consultants committee, arguing that the coalition's healthcare reforms threatened to take us back to the 'grim and unfair' days of the 1930s and 1940s, leaving the NHS an 'increasingly tattered safety net'. He thought that under these proposals, the NHS would become the 'provider of last resort', only used by patients with chronic illnesses who were of no interest to private firms. Ultimately, the return of unequal healthcare could even see provision starting to resemble that of the US, 'where tens of millions of people can't get access to high-quality treatment.'

The underlying message was that our learned 'memories' should provide an antidote to ill-judged contemporary reform: that we should not ignore the lessons from history. The question remains, which history? Do our perceptions of the past translate into useful models to inform or do they, instead, obscure contemporary understanding? What did contemporaries really think of pre-NHS hospital care back then, compared with what ordinary people think of provision now. And if things were so bad, how strong were the demands for reform by 1948?

The propagandist conflation of Lansley's controversial proposals with a history of pre-war neglect and disparity is perhaps not surprising. It fed directly into a widespread anxiety, identified by YouGov in February 2012, that increased competition would make the NHS worse, not better. What people valued most about the NHS was its universal access, free at the point of delivery; what they disliked most about the US system, for example, was its insurance-based utility that promoted widespread health inequality. What was forgotten during the discussions on the 2012 Bill, however, was that before 1939 acute hospital care was delivered primarily by voluntary or local authority hospitals, not by for-profit companies or by the Poor Law authorities. And as we shall see, satisfaction rates with this past service were universally high.

Before 1939, responsibility for hospital services was split between the voluntary and local state sector. Access to the former depended on the cover provided through mutual, low-cost, self-insurance, contributory schemes, frequently organised through the workplace, which for 2d or 3d per week covered members and their families. G. D. H. Cole's wartime inquiry into popular attitudes to welfare provision found such schemes were highly regarded by their working-class members - they gave 'good value', 'good service for payment', 'there was no dislike of contributing'; schemes offered an implicit 'guarantee' of good quality hospital care without the need for direct payment. The middle classes now relied less on private medicine and turned instead to subsidised pay-beds within the voluntary hospital sector. Other current and capital costs were met from philanthropic sources (subscriptions, donations, legacies), and increasingly, from a well-oiled, community-based fundraising machinery; it was the epitome of organic localism in action.

More problematic was the second tier of cover, provided through public hospitals, run either by local Public Assistance Committees (PACs, whose antecedents lay in the Poor Law), or more commonly by local authority Public Health Committees. Some local authorities - particularly the London County Council - proved to be enthusiastic hospital appropriators and spenders, investing heavily in the apparatus of acute medical care; others less so. Traditionally, public hospitals housed the chronic sick and elderly. As today, it was here that many of the major shortfalls could be found. Public hospitals had a statutory responsibility to admit local residents. Too many interwar public hospital wards - notably those still run by PACs - lacked such basic amenities as operating or X-ray facilities.

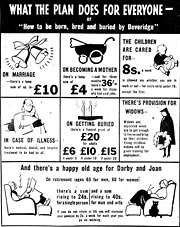

What then of our 'memories' of that past? How accurate are they and how did contemporaries react to reform in 1948? Perhaps the best-known and remembered of all modern British welfare impetuses was William Beveridge's Social Insurance and Allied Services, known as The Beveridge Report. Published in December 1942, this set out the vision for Britain's welfare state. Polling in the weeks following its publication, Gallup found that 92 per cent of the public had heard of the report, and 88 per cent thought it should be implemented. A staggering 636,000 copies of the report were sold (mostly of the abridged version). It also received largely sympathetic media coverage.

Yet the social investigation organisation Mass Observation (MO) found that few members of the public understood the detail beyond the headlines, largely because few people took a detailed interest in even relatively serious news. MO founders Charles Madge and Tom Harrison noted dismissively that 'the mass of people' were both 'unobservant and inarticulate'. Nonetheless, when suitably prompted, 88 per cent of people did think Beveridge's 'outstanding proposal' that 'free' doctor and hospital services should be available to everyone was a good idea. A 1943 Gallup poll revealed that 70 per cent of those surveyed thought a state-run medical service would be beneficial, although few could say why.

Yet health reform was not a general priority. Asked by MO to name the most important topic discussed by the Beveridge Report, those that had a clear opinion (and 40 per cent did not) listed first old age pensions, then family allowances, with health reform coming a poor third. More broadly, rationing, housing, employment, taxes and the cost of living all squeezed out social reform from the top five issues of public concern. It is worth noting, too, that Beveridge strongly favoured offering inducements so that contributory funds, and thus voluntary hospitals, would survive the creation of the Welfare State, although this is nowadays forgotten. He was later to describe contributory schemes as 'one of the remarkable growths in Mutual Aid in modern times'. In his now largely overlooked 1948 polemic, Voluntary Action, he argued: 'It is certain that the spirit of Mutual Aid among all classes which inspired these schemes must continue in one form or another, if the Britain of the future is to be worthy of the past.'

G. D. H. Cole's 1941-2 inquiry also revealed little by way of significant levels of discontent with existing arrangements. He noted that 'some seemed to be quite satisfied in an inarticulate way'. The majority, MO argued, 'when having to decide between the known and possible unknown, choose the thing of which they have experience, even though they might be critical of it'. The most common grievances centred on the standard of GP services, where it was widely believed that private patients received a significantly higher quality of care than those treated under the National Health Insurance Act, 1911. The promise of 'free' treatment under the NHS seemed the biggest inducement.

Such vagaries of public understanding and inner conservatism are familiar today. Ipsos Mori, polling in February 2012, found that detailed awareness of the present NHS reforms was similarly lacking, with two-thirds of those questioned admitting to knowing little or nothing at all about them (see question 13). Where there was an awareness of specifics, it centred primarily on GP commissioning (13 per cent of those sampled). The most common perceptions focused on the supposed cuts to the NHS that would result.

Daily Mirror, 2 December 1942

Reproduced courtesy ©Mirrorpix

How we interpret a popular lack of knowledge, whether in the 1940s or the 2010s, raises interesting questions. Social investigators and pollsters then - like MO, which sympathised with a broadly progressive agenda - explained away inertia in terms of cynicism rather than apathy. The public, it argued, had developed 'a protective device for guarding against further disappointment' - rationalised by an acceptance that 'existing conditions aren't so bad after all or that change might be even worse.' Such stoicism conveniently allowed MO to dismiss the 'fairly large amount of resistance to State interference in the field of medicine'. Yet when surveyed in 1943, roughly half the population were, 'opposed to any major change on the health front', a quarter were 'disinterested', and a 'quarter in favour of State intervention'.

Is it the case then that all major health service reforms are instinctively unpopular or treated with trepidation? According to Ipsos Mori (Feb 2012), despite lacking any detailed knowledge, 38 per cent thought that the Lansley reforms would automatically mean a poorer service for patients, with only 20 per cent linking them to future improvements (see question 15). A YouGov poll, taken in February 2012, found that half of respondents thought the Government should abandon its proposed reforms, with only 19 per cent supporting them.

Timmins has suggested that one of Lansley's major problems was that his reforms were overly complex, and could not be summarised in one or two sentences. Thus, his elaborate discourses were largely overshadowed by negative comment from opponents; his narrative, such as it was, lacked the 'Cradle to the Grave' presentational simplicity of Beveridge - a slogan that has resonated strongly with the public since 1942. In addition, the new NHS was instantly popular. Polling immediately after its formation, Gallup found that 35 per cent thought it was the best single initiative the government had taken since coming into office (the next best being increased pensions: 12 per cent). By the 1960s and 1970s, 75 per cent thought that the NHS gave good value for money. Polling data suggests that this public affection has continued into the twenty-first century. Coupled with rising levels of user-satisfaction, this affection made 'dispassionate debate', in the words of Chris Ham of the King's Fund, 'very difficult'.

Reliable data on public opinion depends on a well-designed sampling programme, and asking sensible questions, rather than those designed to elicit a particular response. A 1939 Gallup poll asked: '1092 hospitals in Great Britain are dependent upon charity for their support. Do you favour continuing this system, or should hospitals be a public service supported by public funds?' Perhaps not surprisingly, only 22 per cent favoured the status quo, whereas 71 per cent favoured state funding. Wartime surveys by the Home Intelligence division of the Ministry of Information found people felt strongly that in future, hospital care should be available to everyone, without the stigma of charity. Charity, as one housewife interviewed by MO noted, was 'rather a lovely word that has come to be rather unpleasant'.

Yet when Gallup later asked whether hospitals should remain voluntary institutions, be run by a public authority or become partly voluntary and partly public, half who had an opinion selected either wholly or partly retaining voluntary provision. Half expressed 'unqualified approval' of voluntary hospitals. An equal number expressed general approval of voluntary work and institutions, but only 'one in three had anything approving to say about charity or charities'. Thus, putting charity and hospital together in the same sentence did not play well in the 1940s, but when relabelled under the voluntary or mutualist caption, support and approval increased significantly.

In 2012, YouGov found that linking competition and privatisation to health reform played equally badly. 'A free health service', wrote Tony Parsons in the Daily Mirror, 'has been handed down by the generation that fought the Second World War to their children, and to their grandchildren... Cameron and Lansley would turn the great good friend of the sick, the poor and the vulnerable into an ally of the money-grabbers, the bean counters and the private sector'. Indeed the Mirror's extensive coverage of the reform bill captures much of the underlying vitriol of the debate: with its personalised attacks - 'Bully Boy Lansley refuses to listen to staff over health proposals' - exposés of 'Secret NHS cuts dossier Tories tried to hide' and the citing of damaging expert opinion - 'Doctors reject dangerous NHS plans'.

This anger spilled out beyond the print media, as the exchange between pensioner June Hautot and Lansley illustrates. The Daily Express noted that there was 'widespread dismay among (Lansley's) colleagues at his inability to quell hostility to his plans.' Why is it, the paper's chief political editor asked, that the 'Prime Minister (David Cameron) has contrived a nightmare combination of circumstances for himself: a reform without a mandate, opposed by powerful professional groups on the key issue on which the Conservative Party is least trusted?' Citing 'insider' party sources, he added that Cameron knew, in his 'heart of hearts', that the Bill was a 'complete disaster' and that Lansley had been 'on life support for a year.' After Lansley was, as the Daily Mail put it, 'spectacularly ditched' in a Cabinet reshuffle, an opinion article by Richard Vize in The Guardian described him as: 'a shocking communicator, from ill-tempered media interviews to the hectoring tone he adopted with the professions.' He 'alienated every interest group and patronised those who disagreed with him.'

If the pre-NHS hospital system was as disparate as suggested, if access was randomised and standards frequently out-dated or haphazard, then comparing the present with our 'dark past' should offer sharp contrasts. Yet Gallup, polling in July 1944, found that 85 per cent of its sample of former patients were satisfied with their hospital treatment. Two-thirds of these had been patients in voluntary hospitals. MO recorded similar levels of approval in London hospitals, with only 19 per cent expressing dissatisfaction. As already noted, the National Insurance-funded GP service - covering working people but not their dependents - was less popular. Here disapproval rates stood five to ten points higher than for hospital services.

The introduction of the new NHS in 1948 saw satisfaction rates rise, but only temporarily. By 1949, satisfaction ratings recorded by Gallup had fallen roughly back to pre-NHS levels. The most frequent 'grumbles' focused, as they had always done, on admission delays, waiting times in outpatient departments, poor food, discourtesy and the condition of hospitals. Poor quality care for the chronic sick and maternity cases provoked the strongest criticism. When, in 1956, a cross-section of patients were asked by the American academic, Paul Gemmill, whether the NHS offered better or worse treatment than before 1948, 36 per cent said better, 13 per cent worse, but significantly, the majority (51 per cent) said 'about the same'. Given the alleged deficiencies of the pre-NHS GP service, this did not reflect well on the NHS. By the 1960s, Gallup polls found satisfaction rates still stood at around 80 per cent. The issues about which people were concerned, and the chief problems identified, remained remarkably constant.

What of the recent past? The most comprehensive time series, the British Social Attitudes surveys (BSA), reveals significant variations in patient approval ratings from 1983-2011. In-patient satisfaction averaged 61 per cent across the three decades, while for out-patients, until 2003, it was slightly lower (see Figure 1, below). Those neither satisfied nor dissatisfied averaged 18-20 per cent across time. The most striking recent improvement centred on the NHS's overall approval ratings. When the public were asked by BSA in 1996 and 1997 how satisfied or dissatisfied they were with the way in which the NHS was managed, only 35 per cent responded favourably. In January 2002 the Daily Telegraph had reported on the basis of a Gallup poll that public satisfaction with the NHS was at 'an all-time low despite the extra billions pumped into the system since Labour came to power in 1997.' Forty per cent said they would prefer to 'go private' if they could, forty per cent thought the NHS was getting worse, and 20 per cent thought it a failure. Yet, by 2010 this situation had changed radically. Now 70 per cent expressed satisfaction with the way the NHS was run, undermining the case for substantive reform. The years preceding 2010 had seen sustained increases in investment, with waiting times at an all-time low. It was no coincidence that as resources and key patient performance indicators improved, so too did overall public satisfaction (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: NHS satisfaction ratings 1986-2011

Figure 2: NHS satisfaction ratings v. net expenditure as % of UK GDP 1983-2010

In 2002, even as the Daily Telegraph described a failing service, satisfaction rates based on the treatments received from either GPs or hospitals still remained high. Ten years later, an Ipsos Mori tracker poll covering 2000-2011 identified that people were significantly (roughly 10 to 15 per cent) happier with their local NHS service than with the NHS nationally. Thus, satisfaction rates with the treatment or service experienced locally was always higher than with broader, abstract rankings of the quality of NHS provision. What is noticeable, given the rhetoric of past shortcomings, is that approval rates before and after the establishment of the NHS were roughly congruent, and easily comparable, with more recent satisfaction levels. Satisfaction with the general management of voluntary hospitals was also high, judged by the readings from hospital records. Indeed, it is tempting to speculate that satisfaction rates were higher before 1948 than, say, in the 1980s and mid-1990s, when approval rates hovered at 35 to 45 per cent (Figure 1). One certainty, however, is that the Lansley reforms overturned a decade of rising confidence in the NHS, although obviously how this plays out in future opinion polls has yet to be determined.

The popular history of healthcare is commonly built around misconceptions, fashioned by contemporary concerns and agendas. Nonetheless, according to Ipsos Mori, the 'NHS as a whole, and in particular the principles it embodies, remains a huge source of latent pride', perceived by the British public to be 'one of the best of its kind in the world'. In itself this might be thought a relatively harmless transmission of a much loved national story. Yet an analysis of public opinion about pre-NHS hospital healthcare suggests widespread approval and satisfaction, comparable with that of the post-war decades under the NHS. Notwithstanding this, the very act of questioning the 'folk history' of the NHS is problematic because it jars so strongly with our imagined past. As Virginia Berridge has found in research for History & Policy, politicians and policymakers cite history selectively: 'Invoking Nye Bevan is a cottage industry among [New Labour] health ministers', she concludes, because it becomes part of the 'necessary dynamic of policymaking', a starting point and a populist benchmark for contemporary narratives.

In the recent past, those proposing and opposing health reforms have put forward equally selective interpretations of history. In this context, opinion and social survey data offer us valuable insights and correctives; they let us recapture what ordinary people really thought about critical issues like health provision. Powerful mythic histories, such as that surrounding the founding of the NHS, offer significant barriers to change or objectivity in health policy making. Fear of returning to an imagined, bleak and dangerous 'health past' plays strongly, not simply because that past is unknown or caricatured, but because it is also associated - incorrectly - with charitable or privatised medicine (neither universal nor 'free at the point of use').

It would be near-impossible now to recreate the vibrant civil society needed to fund voluntary provision in the way that it existed before 1939. Attitudes have changed; structures many years in the making have been dissolved. The call here is simpler, more basic: to show that inter-war, multi-sourced hospital provision had its own significant levels of vitality, in terms of patient care, community involvement and financial stability. We should resist the temptation to exaggerate the disjuncture between a pre-reformed health service, and the nationalised system with which we are familiar. Then, perhaps, we can break our intuitive resistance to all NHS reform as threatening to return us to a dark past, and focus instead on the merits, and demerits, of the contemporary case. Recent reforms deserve to be scrutinised and, in some respects, criticised, but not on the basis of an imagined historical past.

Today, popular understanding of the new health reforms remains at best partial, a situation not helped by poor communication by the Department of Health and the absence of a clear rationale for change. Yet historically, a lack of detailed, public understanding for reform is not unusual. Even the Beveridge Report was only understood in the most general of headline terms. The lack of detailed public understanding, however, should not be read as lack of public opinion. In the 2010s, as in the 1940s, people have clear and strong views about their experiences of health services, which should not be dismissed or ignored simply because of a lack of detailed knowledge of particular reforms.

The imagining of our health past reduces the space for policy innovations and generates significant resistance to change amongst the public and the broader body politic. In fact, the differences between positive readings by contemporaries of health service provision, then and now, are significantly less than are imagined today. The inter-war period marked the beginnings of universal health care, and a comprehensive hospital service offered through multi-sector providers, where regional and social disparities in coverage and treatment were reduced significantly. Cheap hospital health insurance was particularly well regarded; patient satisfaction levels remained high. Fear of change was deeply embedded in the public psyche then, as now. Yet this is not how our health past is remembered, nor is it how this national story is retold.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Paris, 1957: trans. London 1972)

William Beveridge, Social Insurance and Allied Services Cmd 6404, (London, 1942).

William Beveridge, Voluntary Action: A Report on the Methods of Social Advance (London, 1948)

Paul Gemmill, 'The British Health Service Today', New England Journal of Medicine, pp.256 (1958), 19-23

Chris Ham and Nick Timmins, Never Again? The story of the Health and Social Care Act 2012, video available on the Institute for Government website

José Harris, 'Did British Workers Want the Welfare State? G. D. H. Cole's Survey of 1942', in J. Winter, ed., The Working Class in Modern British History (Cambridge, 1983), 200-14

Nick Hayes, 'Did we really want a National Health Service? Hospitals, Patients and Public Opinions before 1948', English Historical Review CXXVII (2012), pp.625-61

Ipsos Mori, Understanding Public and Patient Attitudes to the NHS (London, 2006); Public Perceptions of the NHS and Social Care (London, 2012)

King's Fund, Public Satisfaction with the NHS and its Services (London, 2012)

Nick Timmins, Never Again? The story of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 (London, 2012)

Sign up to receive announcements on events, the latest research and more!

We will never send spam and you can unsubscribe any time.

H&P is based at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, University of London.

We are the only project in the UK providing access to an international network of more than 500 historians with a broad range of expertise. H&P offers a range of resources for historians, policy makers and journalists.